Ober's Island: The Mallard

Rainy Lake, Minnesota

The Ernest Oberholtzer Foundation

“My home all these years has been an acre and a half rocky island in Rainy Lake, half a mile from the Canadian border.” –Ober

Is there a lawn to be mowed on your island, asked the young man? Ober smiled and said a grain merchant visited his island once. After walking around it, he growled, I wouldn’t live on this damned rock heap for all the money in the world. The trouble with you, Ober replied, is that you are a grain man. You judge the Mallard by how much grain it would grow. If you were fond of blueberries, you would call it the Promised Land!

Editor. "Atisokan: His Rainy Lake,” The Rainy Lake Chronicle, 9/2/1978:5.

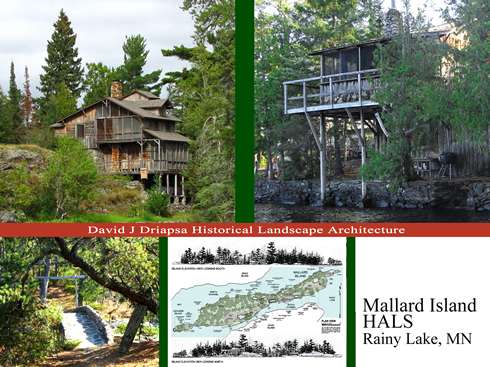

David Driapsa conducted a Historic American Landscapes Survey of cultural landscape on Mallard Island, the island estate of conservationist, artic explorer, Wilderness Society co-founder, and landscape architect Ernest Carl Oberholtzer.

The Ernest C. Oberholtzer Rainy Lake Historic District is nationally significant under national register evaluation criteria B, recognizing the contributions of Ernest Oberholtzer as a pioneer in wilderness conservation. He was a conservationist, explorer, and wilderness philosopher of the Rainy Lake area. His legacy is associated with the Quetico-Superior Council, of which he was a founder (1928) and president; the President's Quetico-Superior Committee, on which he served from 1934-1968; as an articulate voice of authority in the struggle to preserve wilderness character in the border lakes region along the international boundary between the United States and Canada; and as a founder and officer (1937-1967) of the Wilderness Society.”

Ernest Carl Oberholtzer was born February 6, 1884, in Davenport, Iowa, and died June 6, 1977, in International Falls, Minnesota. He lived most of his adult life on Mallard Island in Rainy Lake near Ranier, in northern Minnesota.

Oberholtzer was educated at Harvard University, receiving a broad liberal education, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1907. During his senior year, Oberholtzer studied landscape architecture under the tutelage of Fredrick Law Olmsted, Jr. He then continued an additional year at Harvard in the newly established graduate school of landscape architecture under the tutelage of James Sturgis Pray.

The Ernest C. Oberholtzer Rainy Lake Historic District nomination did not document the cultural landscape of Mallard Island in detail. Yet the cultural landscape remains a monument to the genius of Ernest Oberholtzer in the area of landscape architecture. This island is significant under national register evaluation criteria C, as a distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction, but its distinctive characteristics are of a type, period, and construction that represent the work of a master and possess his high artistic values.

The cultural landscape of Mallard Island is significant at the national level as embodying the type and period of a rare remaining example of a personal estate created by a student of the world’s first professional graduate course in landscape architecture education. It is significant at the state level as embodying the type and period of rustic landscape associated with the National Park Service, Civilian Conservation Corps and state recreational development in Minnesota. Mallard Island also is significant at the local level as embodying the historic context for tourism and recreational development in the northern border lakes from the 1880s through the 1950s.

Mallard Island is a narrow mass of rock protruding from Rainy Lake. The one and a half acre island stretches 1,300-foot from end to end, and 150 feet across at its widest point. The highest point of granite rises only twenty-four feet above the lake level.

Oberholtzer biographer Joe Paddock described Mallard Island as a spiritual place sacred to the Ojibwe Indians. Indeed it seems spiritual. When I departed from my first visit, the sun broke through the grey day to illuminate Mallard Island, and a bald eagle circled above.

When approaching the island from the lake, the many trees that line the shore slowly reveal the buildings. My first impression upon stepping foot on land was that this is a very special place.

It was only after Oberholtzer Foundation Board member Diana Tessari gave me a tour of the island that I realized the extent of development on what first appeared a wooded island. Oberholtzer’s mastery of landscape architectural space makes the small island seem expansive. Rustic buildings blend into the landscape. Some buildings stand-alone and others are grouped in clusters. Oberholtzer occupied Mallard Island for a half century creating what appears a small folk village. It is an integrated complex of domestic buildings and related structures.

The island is developed as a rustic recreational camp type, of the early twentieth century period. Individual buildings are ephemeral constructions assembled from natural wood and stone materials purchased or gathered locally or recycled from earlier buildings. The main house – also called the Old Man River House or simply Ober’s House – is a substantial three-story structure built into the rock face of a cliff. The natural wood and stone building rises three stores from waterfront terraces to the highest point on the island. It possesses a dignity of rustic design and the construction is the work of Rainy Lake artisan Emil Johnson.

The cultural landscapes if most distinguishable entity of Mallard Island. The spatial organization of building components and land patterns; adaptations of buildings, structures, and objects to the natural topography; and choreography of terraces, places, views, and paths is a work of landscape architecture of high artistic value. The many buildings and structures, terraces and gardens, and walks are carefully sited and choreographed upon the rocky island, and hand-crafted of natural materials that blend into nature.

The cultural landscape is the character-defining feature of Mallard Island. The spatial organization of Ober’s “little village,” his carefully integrated buildings and structures upon the topography, the creation of useable spaces that blend imperceptibly into the native setting is a masterwork of landscape architecture.